Thirty-six years after she gave birth to a baby girl and placed her for adoption, a woman learned that the child had been missing for 21 years.

That’s not the plot of a mystery novel or a fictional film. It’s how the docu-series Into the Fire: The Lost Daughter begins. Out on Netflix Sep. 12, the two-part series follows Cathy Terkanian’s quest to find her daughter, Aundria Bowman. While she did not raise the child, Terkanian’s motherly instinct comes through in the series, in the way she connects with the friends of her daughter and the online sleuths who help her crack the case. As Terkanian sums up her motivation for the search, “I saw the fire, and I walked right in it.”

Here’s how Into the Fire: The Lost Daughter uncovers what happened to Bowman and how her birth mother became involved in the search.

The search for a lost daughter

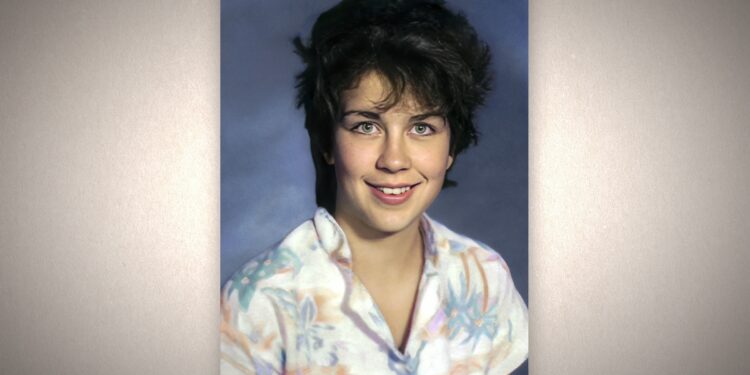

Terkanian gave birth to Bowman in 1974 when she was 16. In the series, she makes it clear that she did not want to give her baby up, but that her mother persuaded her to do so, convincing her that at a young age, she couldn’t handle the responsibility. It was a closed adoption, and Terkanian didn’t try to look for the child, figuring that they might connect when she was older.

But she never got the chance. In April 2010, Terkanian received a letter from the adoption agency informing her that the child had gone missing when she was 14 years old, in 1989. An unidentified body had been found next to a cornfield, and the police needed Terkanian’s DNA to see if it was her daughter.

It was not a match, but Terkanian became determined to find her daughter. She knew her daughter’s birth date, and that’s all she needed to bring up her file in the missing persons section of the Michigan state police department. She learned that her daughter was renamed Aundria Michelle Bowman, and that she lived in Hamilton, Michigan.

When she started a Facebook page called “Find Aundria Bowman,” she started getting flooded with messages of support and learned more about her daughter. She learned that the adoptive parents were Dennis and Brenda Bowman. She connected with Carl Koppelman, an accountant who searched for missing persons in his spare time and appears in the docu-series. Also featured is a child kidnapping survivor, Metta McLeod, who reached out to Terkanian because she believed that Dennis looked like the same guy who kidnapped her as a child—though it could never be proven—and Terkanian became like a mother to McLeod.

The docu-series depicts a troubling picture of life at home for Aundria. During filming, Terkanian connected in person for the first time with people she met online who knew Aundria growing up, who claimed her father would hit her. One describes being over for dinner one night and the parents eating hamburgers, while Aundria and her friend were given sandwiches with just ketchup, mustard, and relish inside. The friend recalled that when Aundria told her friend that was all she was allowed to eat, Dennis came over and hit her so hard she almost fell off of her chair.

How Aundria Bowman was found

Terkanian did important work to keep the case top of mind for law enforcement. But to figure out what happened to her, law enforcement had to solve another murder case first.

A detective, Jon Smith, who was charged with investigating cold cases for the Norfolk, Virginia police department, re-examined the case of the 1980 rape and murder of a local woman named Kathleen Doyle, the wife of a U.S. navy pilot. There was a bedspread from the crime scene that had been preserved, and Dennis Bowman came up as a possible DNA match. After investigating his criminal history, Smith learned that Dennis did a two-week stint with the Navy in Norfolk. He went to visit Dennis, who agreed to a DNA swab. It matched the DNA on the bedspread. Dennis was arrested in 2019, and confessed to the murder.

At one point, Dennis requested to meet with his wife Brenda and footage of the conversation is in the docu-series. He told authorities to have their cameras rolling. “Aundria’s dead,” he tells her. “She’s been dead from the start.”

Then he admits that he got into an argument with Aundria at home, and she tried to run away, saying she’d tell the police that he molested her. He says he hit her, and she fell backwards down the stairwell of their home. He said he cut her legs off, stuffed the remains in a barrel, and then put the barrel out with the neighbors’ trash cans.

But throughout the docu-series, Dennis changes his story in letters—read by an actor—and phone calls exchanged with Brenda while he was in prison. In one key phone call excerpted in the film, he tells Brenda that Aundria is actually buried in her backyard. The authorities sent a bulldozer to the property, and the bulldozer turned up the barrel that Dennis was talking about. The remains were found in a trash can of diapers and a Peppermint Pattie candy wrapper that had the date 1989, the year Aundria disappeared.

Ryan White, director of Into the Fire: The Lost Daughter, argues that Dennis only confessed to the murder when he was told he could serve his life sentences in Michigan—closer to his wife and daughter—rather than in Virginia. Early on in the series, there are snippets from police interviews with Dennis in which he vehemently denied killing Aundria. “I still am not sure that Dennis has ever told the full truth about what happened to Aundria,” White says.

On Feb. 7, 2022, Dennis was sentenced to second degree murder. He is now serving two life sentences for the murders of Aundria and Doyle in a Virginia prison.

The documentary ends with Terkanian hysterical about having to meet the child she gave birth to in the worst possible way—by receiving half of her cremated remains, while the other half went to her adoptive mother Brenda. (Brenda Bowman did not provide a comment for the series.)

The filmmakers hope that a docu-series on Dennis on a platform on a big platform like Netflix will inspire those pursuing cold cases to persevere and inspire anyone else who has encountered Dennis to come forward with their stories.

“It’s very important that his face is out there,” White says. “We’re hopeful that, in the documentary coming out, others might be able to connect some dots that have never been connected, just like Cathy did.”