Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn early August, Pablo González was taken from a prison in Poland and flown to Moscow on a plane carrying Russian deep-cover agents, hackers and a hitman for the FSB intelligence service.

The group was met at the airport by a military guard, red carpet and Vladimir Putin – thanking them for their loyal service to the country.

Video footage from that night in Moscow shows Mr González smiling as he shakes hands with President Putin at the foot of the plane steps. Black-bearded, with a shaven and shiny head, he’s wearing a Star Wars T-shirt that declares “Your Empire Needs You”.

Known by his Russian friends as “Pablo, the Basque journalist”, the 42-year-old was part of a major prisoner swap for Westerners held in Russian jails and Russian dissidents.

In the group freed by Vladimir Putin were two opposition activists Mr González was accused of spying on.

He’d been arrested in Poland in 2022 for alleged espionage.

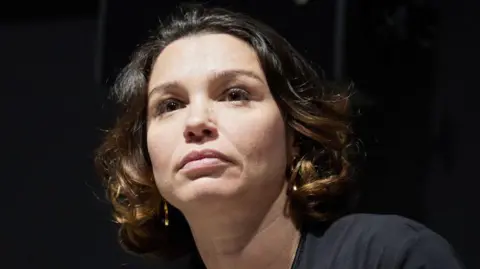

“I got my first suspicions in 2019. It just dawned on me,” Zhanna Nemtsova tells me, in the first interview she’s given about the man who spied on her.

The two met in 2016 at an event about the investigation into her father’s murder. Boris Nemtsov, a staunch opponent of Vladimir Putin, had been assassinated a year earlier, right beside the Kremlin.

His daughter – herself a vocal Putin critic – eventually moved to Europe for safety.

That day in Strasbourg, Pablo González asked Ms Nemtsova for an interview for a newspaper in the Basque region. She refused, at first. But the journalist – Spanish, with Russian roots – gradually became something of a fixture in her circle: attending events, taping interviews, mingling.

Looking back, Ms Nemtsova remembers becoming wary.

“I shared my suspicions with a couple of people and they were like, ‘No, this is nonsense!’ People regard you as crazy if you bring up some things. They can think you paranoid.

“But I was absolutely right.”

That’s why she’s decided to speak out openly now.

“I want other people to be very careful,” Zhanna Nemtsova explains. “The threat is not something you can just read in books or watch at the movies. It’s very close.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMr González was only formally charged with espionage a week after he left Poland, flown to Moscow as part of the August prisoner swap. By then, he’d spent well over two years locked up, awaiting trial.

All along, Polish prosecutors have deflected questions about the case and the process. Intelligence sources remain tight-lipped. The Polish lawyer who first represented Mr González says he can’t comment.

By the time of his arrest, Mr González had been living in Warsaw for at least three years, much of that time with his Polish girlfriend. He was a freelance journalist, working mostly for Spanish-language press.

He reported from the war in Nagorno-Karabakh and travelled to Ukraine. At some point, he joined a media trip to Syria run by the Russian defence ministry, always very selective about who it takes.

It was in 2022 that he was detained, briefly, in Ukraine, though the SBU security service there won’t divulge any details. Then, on 28 February, Mr González was arrested in Przemysl, eastern Poland, where he was part of the media pack covering the start of Russia’s all-out war on Ukraine.

The trigger for the arrest has not been made public.

Reuters

ReutersLast year, Zhanna Nemtsova was shown evidence of Mr González’s activity as part of the criminal investigation.

“I have no doubt he was a spy. I am sure, 100%,” she told me this week.

Ms Nemtsova is banned by a non-disclosure agreement from sharing details of the evidence. As a result, she’s had to watch people continue to profess that Mr González is innocent.

“It’s scary. We shouldn’t downplay this. These people have no moral scruples. They regard you as their enemies,” she warns, referring to Russian intelligence agents.

Although Ms Nemtsova says she never trusted Mr González as a true friend, he did manage to insert himself into her circle. He was informing on the group from the start, she says.

“He can be very charming, he knows how to communicate with people, make them feel at ease.”

Her ex-husband, Pavel Elizarov, agrees. He and Mr González were “quite close for some period of time”. He would visit him in Spain, talk politics and do tourism. He introduced others to his friend.

Ilya Yashin, another prominent activist, went to football matches with Mr González in Spain and even coat shopping. When Mr González was released in the prisoner swap, Mr Yashin was one of the trades: he’d been imprisoned in Russia for condemning the war on Ukraine.

Vadim Prokhorov, the Nemtsov family lawyer, recalls another detail.

“He drank like a Russian,” Mr Prokhorov told me. “He could hold his drink without falling over. We should have suspected him back then!”

EPA

EPAWe did ask to interview Mr González via his wife, who lives in Spain and has been his most avid supporter. So far, he hasn’t replied.

Instead, he appeared on Kremlin-controlled television, filmed wandering through a Moscow suburb, reminiscing in perfect Russian about sledging on cardboard as a child.

He was born, he explains, Pavel Rubtsov – still the name in his Russian passport.

He became Pablo González when he moved to Spain with his mother in 1991. His grandfather had been evacuated to the USSR during the Spanish Civil War, so Pavel and his mother were entitled to Spanish citizenship.

It all made him ideal recruitment material for Russian intelligence, but the state TV report declared that Poland had no evidence of that.

“They threatened and pressured me,” Mr González says, in his extremely deep voice. “I asked, ‘What did I do?’ and they said, ‘You know.’ But I didn’t.”

No-one I’ve interviewed has characterised Mr González as a Putin fan, although Zhanna Nemtsova says she and he were on “different sides of the political spectrum”.

“I didn’t get any pro-Russian vibe off him,” a Polish contact said.

But on Russian TV, Mr González is quite clearly excited as he describes meeting “Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin” at Vnukovo airport in Moscow.

Coming down the plane steps, he says, he was “practising” all the way how to greet his president. “I wanted to be sure it was a strong, manly handshake,” Mr González explains, with a big grin.

Russia TV shows freed prisoners boarding plane after swap

The BBC has not had direct access to any of the material in this case. But we have interviewed reliable sources whose accounts, taken together, reveal that Pablo González was informing on a number of people in Europe.

When he was detained, Polish investigators discovered reports detailing the movements, contacts and profiles of people ranging over several years.

Russian opposition activists were one target, including those close to Zhanna Nemtsova. There’s a report on at least one Polish citizen, as well as students of a journalism summer school run by Ms Nemtsova. Investigators also found emails that Mr González had copied from a laptop he had been lent.

We don’t know who these reports were sent to, but they list expenses incurred in gathering information, including transport costs. “There were a lot of details, including what they ate for lunch,” the BBC was told.

In some cases, that source says, questions have been added, apparently by a superior seeking clarification or more detail.

One of the reports concerns the Russian defence ministry press trip to Syria that Mr González went on, though its main focus is to criticise the ministry for poor organisation of the tour.

The official charge sheet accuses Mr González of espionage – namely, providing intelligence, spreading disinformation and “conducting operational reconnaissance” for Russian military intelligence, the GRU.

We don’t know what other evidence there might be, but the value of what he gathered on the Russian opposition is unclear.

I was told that some reports are “sloppy” and include information taken from the internet. “Some were really wordy, with 10 pages instead of one. Probably to get more funding,” the source thought.

The first part matches the comments of a close friend of Mr González who told me he was “a bit lazy”.

The BBC also understands that the accuracy of the reports deteriorates notably after 2018, with fewer notes or corrections by a senior officer, or handler. It may be coincidental, but that’s when large numbers of Russian intelligence assets were expelled from Europe, after double-agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter were poisoned in the British city of Salisbury.

And although Russian activists who socialised with “Pablo, the Basque journalist” were shocked to learn he’d betrayed them, they doubt he had access to sensitive information.

“We are not in the habit of sharing this information with anyone, as we’ve always known we could face such problems,” Zhanna Nemtsova confirms.

“Everything we said to him, we’d say to anyone else in public,” opposition politician Vladimir Kara-Murza told me after his release as part of the same prisoner swap.

Reuters

ReutersOne source sought to downplay the case against Mr González, describing the contents of the reports as “not serious”. But Ms Nemtsova – whose father was murdered in Moscow for his politics – strongly disagrees.

“His words were important for the GRU [Russian military intelligence]. They might have led to serious consequences. This does not suggest that Pablo himself would do some damage. But they have other people who do this.

“That’s why this is serious.”

When Mr González was detained, there was a flurry of protest over accusing a journalist of espionage. The EU had significant concerns about the rule of law under the previous Polish government, while groups such as Reporters Without Borders called for Mr González to be brought to trial, allowed to defend himself against any evidence, or be set free.

“I thought maybe they were mistaken about the arrest,” a Polish journalist who knew Mr González remembers his own initial doubts. “I thought maybe it was just to show the government were doing stuff about Russia.”

As Mr González was never convicted, his staunchest supporters still argue that Poland has “got away” with an injustice. But most were silenced by last month’s prisoner swap and the ceremonial welcome in Moscow.

The government in Madrid has been notably quiet on the case, in public, from the start.

“But that prisoner exchange, and González’s reception, are the reply to everything,” one official there told me. As she put it, it would be very odd for Vladimir Putin – crusher of the free media – to “save” a mere journalist.

Weeks after Mr González was returned to Moscow, the spy scandal is still causing headaches for Ms Nemtsova.

In 2018 and 2019, the foundation she set up after her father’s killing invited “Pablo, the Basque journalist” to Prague to give a lecture on war reporting. The summer school for young journalists was hosted by Charles University.

Now Czech media have declared that academia has been “infiltrated”, prompting a PhD student to write a dramatic letter to the university Arts Faculty, warning that the Nemtsov Foundation may pose a security threat “to the entire Czech Republic”.

The student, Aliaksandr Parshankou, suggested suspending a Russian Studies MA, supported by Ms Nemtsova’s group, pending an investigation. He told the BBC the course was “by definition a point of attraction for Putin” and called for it to carry a warning that the safety of students “cannot be guaranteed”.

Ms Nemtsova calls the student’s claims “groundless and manipulative” and he admits he has no actual evidence. But the foundation is part of the legacy of Ms Nemtsova’s father and she fears the aim is to “kick us out of the faculty”.

Reuters

Reuters“I am a victim of espionage,” she protested. “It can happen to people like me, but that doesn’t mean we represent a threat to the Czech Republic.”

Pablo González was flown back to Moscow by Russia, where his passport identifies him as Pavel Rubtsov.

Spain does not deprive people of citizenship, even those suspected of espionage. But Mr González would have to reapply for his Spanish passport.

The chances of him heading there seem slim while there’s a case for espionage open in the EU. It’s unclear how long that case might be left pending.

As for visiting his sons there, an official in Madrid was clear: “They are free to go and see him in Moscow.”

Once an intelligence agent is unmasked, their career options and movements are limited.

Other Russians who’ve followed a similar path have ended up starring on state-controlled TV. Perhaps Pablo will restyle himself as Pavel, and find himself praising Vladimir Putin a lot more.

As for Zhanna Nemtsova, she admits she’s even more cautious about who she deals with.

“Now I always think about security,” she told me. “I did think about my security before, because I left Russia. But I didn’t think about security in Europe. Now of course, I do. And I am careful.”