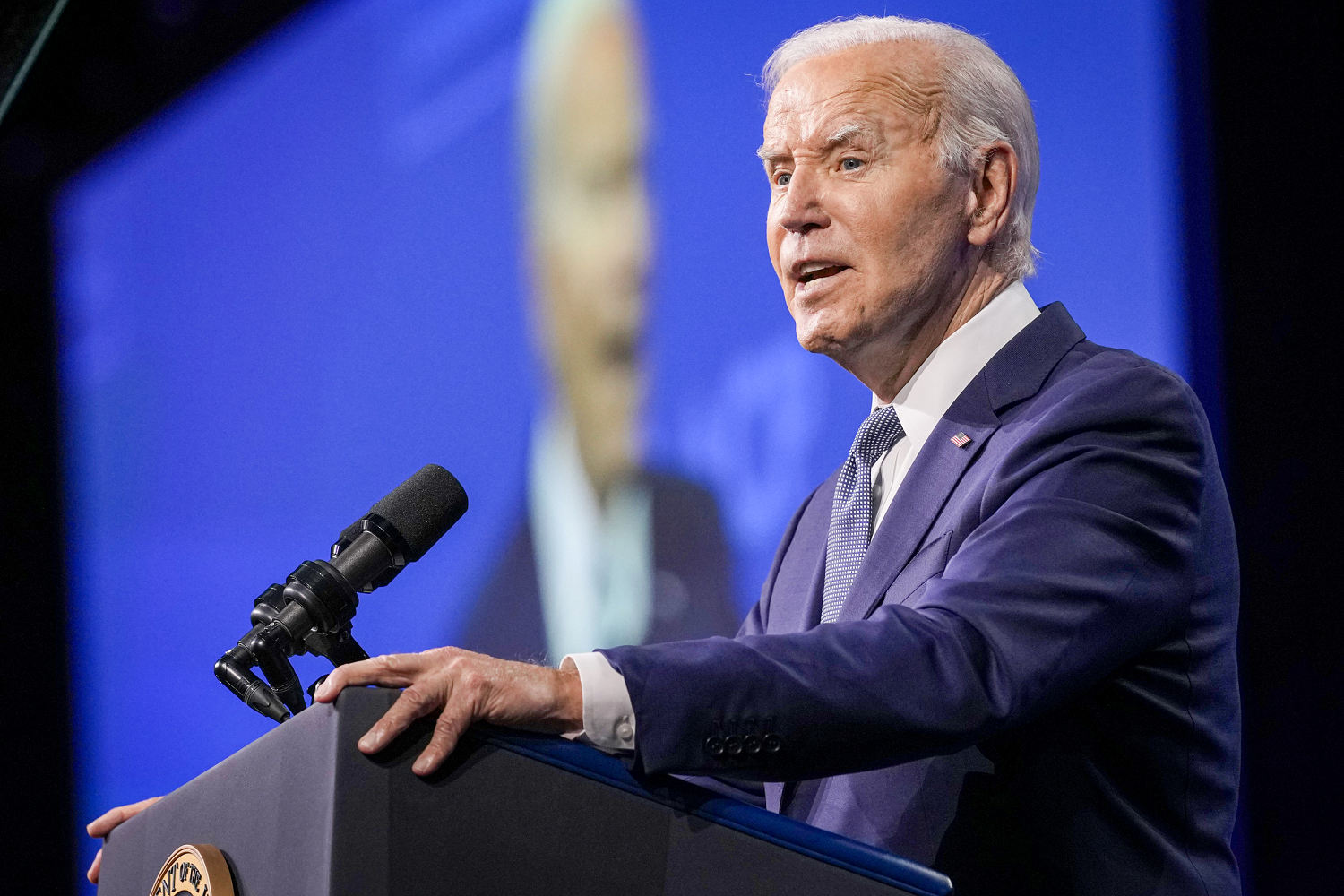

The Democratic pressure campaign to convince President Joe Biden to get off the ticket is rushing to get ahead of deadlines that would turn a political fight into a legal one, due to state laws on ballot certification and vacancies.

Democrats are still on course to formally nominate the president again during the first week of August at a virtual delegate roll call vote before their convention later that month. And while party rules provide a clear path for Democrats to replace Biden before or after that vote, a decision to replace him for political reasons later than that gets into thorny territory, effectively becoming a lost cause by early September.

In short, Democrats may have only days after their convention to finalize their nominee or else they risk being left off the ballot in key states, risking key Electoral College votes and their ability to win the presidency along with it. By early September, trying to put a new presidential candidate on the ballot is no longer solely up to a national party once state laws on ballot certification and ballot vacancies go into effect.

“The sooner it happens, the less fraught the situation will be,” said Rebecca Green, an associate director of law and co-director of the Election Law Program at the William & Mary Law School.

“It is generally the case that parties have flexibility to replace candidates until the ballots are printed,” Green, who is also a member of the National Task Force on Election Crises, continued. After that, she added, “things get more difficult because you’re running up against state laws.”

Many state deadlines aren’t until closer to the election, and many state laws are more flexible governing vacancies on a ticket in the case of a serious illness or death.

But swapping out the presidential nominee for political reasons after early September would jeopardize a party’s ability to win states with stricter laws, such as Maine and Wisconsin — both of which are likely must-wins for Democrats — and others the later a potential vacancy were to occur.

Some election experts, both nonpartisan and Democratic-aligned, say they feel confident that the party could overcome legal challenges in the courts and with the help of friendly state legislatures. But several battleground states are controlled by conservatives who might be less interested in helping Democrats manage a political crisis. And conservatives are already spinning up an effort to fight in court over a potential attempt to replace Biden, while Democrats are already planning to retool their nominating process to sidestep legal questions in at least one state, a clear sign that they don’t want to leave things to chance.

With electoral college margins as tight as they are for Democrats, an attempt to replace Biden in the weeks after the convention could risk the presidential race entirely.

How the Democratic Party’s rules work

Party rules make it virtually impossible to replace Biden unless he steps aside. But some Democratic leaders have been delivering “blunt” messages to Biden about his political standing and the broader implications for the party if he remains the nominee.

If Biden were to step aside now, it could get messy, but the rules are clear: Whoever wins the majority of the voting convention delegates wins the nomination.

If Biden dropped out of the race after being formally named the nominee, the rules cover that, too. A group of Democratic Party leaders would meet to recommend a replacement, and under current rules, a majority of Democratic National Committee members — not convention delegates — would need to vote to approve it.

Where state law takes over from party rules

But once state ballot certification and printing deadlines come into play, that whole process gets remarkably more complicated — particularly after a convention toward the end of August.

Each state has different rules governing when its general election ballot is certified; what, if any, scenarios allow for a party to replace its nominee on that ballot; and even whether a candidate who has withdrawn (or died) is eligible to win votes at all.

On top of that, there’s another complicating factor: “faithless electors” laws on the books in more than 30 states and the District of Columbia.

Those laws were generally written to ensure that the voters in the Electoral College, which technically elects the president, reflect the will of the people in each state, so the electors can’t freelance by voting for someone else. In some cases, these laws could provide a lifeline for a political party whose presidential candidate couldn’t be placed on the ballot in time. But in others, the law could prevent a presidential elector from voting for anyone except their party’s listed candidate on the ballot — even if that candidate has already withdrawn from the race.

It’s a complicated tapestry of state laws — some clear, some less so, and many of them untested in court, particularly for such a weighty scenario. And while a tragedy like a candidate dying or becoming incapacitated would provide a party with more wiggle room, there’s less flexibility in state law for a party to replace a nominee late in the game for political reasons only.

Take Maine, for example, where state law says a general election candidate can’t be replaced within 70 days of an election — Aug. 27 this year — except in the case of catastrophic illness or death. Maine laws governing presidential electors don’t clearly give those electors freedom to vote for a replacement candidate if the original one wasn’t on the ballot. Altogether, that means any attempt to replace a nominee for political reasons after that 70-day cutoff point could jeopardize a party’s ability to win Maine’s Electoral College votes.

“If the president is going to step aside, it would just go a lot more smoothly if he were to step out ahead of the convention,” said Daniel Walker, a Maine-based election lawyer who works with Democrats.

Walker added he believed that in the hypothetical where Democrats replaced their nominee for political reasons after Maine’s deadline, the party would have potential legislative or legal options to get them on the ballot. But he acknowledged those options would would likely spark legal challenges.

In Wisconsin, the deadline for political parties to certify the names of their presidential candidates is Sept. 3. After that, the state code says “the name of that person shall appear upon the ballot except in case of death of the person.” And while the state law governing presidential electors doesn’t require an elector to vote for a candidate who has since died, it again raises serious questions about whether presidential electors can vote for a replacement nominee who wasn’t properly replaced on Wisconsin ballots, and an attempt to swap a candidate out after that date for a reason other than death would, again, spark near-certain lawsuits.

Both states are likely necessary for any Democrat on the path to the 270 Electoral College votes, and there are plausible scenarios in which losing Maine’s four Electoral College votes keeps a Democrat just shy of the winning threshold.

Other states have deadlines later in the calendar, but some are quite rigid.

For example, Colorado allows for a withdrawal and replacement of a nominee until the “earliest day to mail general election ballots” in October. Any withdrawal after that date would lead to votes cast for that candidate being deemed invalid.

In Virginia, nominees can be replaced up to 60 days before a general election (or 25 days in the case of death). But presidential electors appear to be required to vote for the nominee on the ballot pursuant to those rules, so a late withdrawal would jeopardize the ability to win here, too.

Any attempt to replace the nominee later in September would also risk running into federal law, which requires ballots be sent to U.S. military and overseas voters by Sept. 21, adding another legal wrinkle.

Ultimately, it’s likely that an attempt to replace a nominee for political reasons, and possibly for legitimate health reasons, too, would almost certainly lead to widespread and unpredictable lawsuits in states across the country that could wind up at the Supreme Court, with its 6-3 conservative majority.

Depending on the specific circumstances, Democrats would likely mount a massive legal effort aimed at ensuring their replacement nominee has the ballot access required to win the presidency, and Republican groups like the Heritage Foundation have made clear they’d mount a similar legal effort in response.

And that’s why Democrats are trying to settle their questions about Biden now.