With limited data on how environmental stressors — from poor water quality to rising temperatures to contagious diseases — may harm people living and working in U.S. prisons, legislation introduced Thursday in Congress seeks to begin filling in the gaps.

The Democratic-sponsored Environmental Health in Prisons Act would require the federal government to install an independent advisory panel that could conduct related research at all federal prisons, jails and detention centers, recommend policies to mitigate environmental threats, offer reports about those facilities and outline protective measures.

The bill says its goal is to “improve the environmental health outcomes” for people in these facilities, hundreds of which are located within 3 miles of Superfund sites with histories of toxic waste and pollutants, according to a 2017 study.

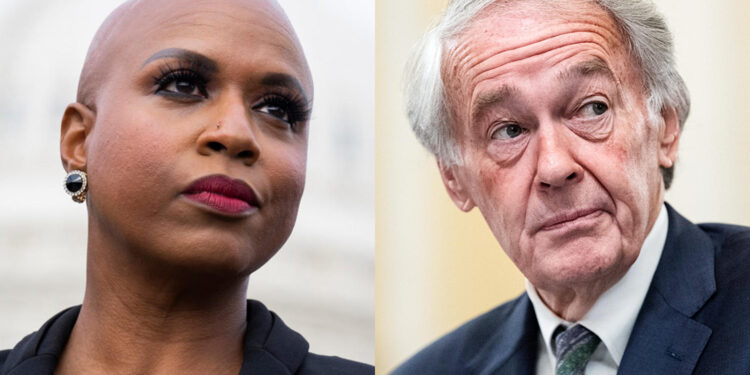

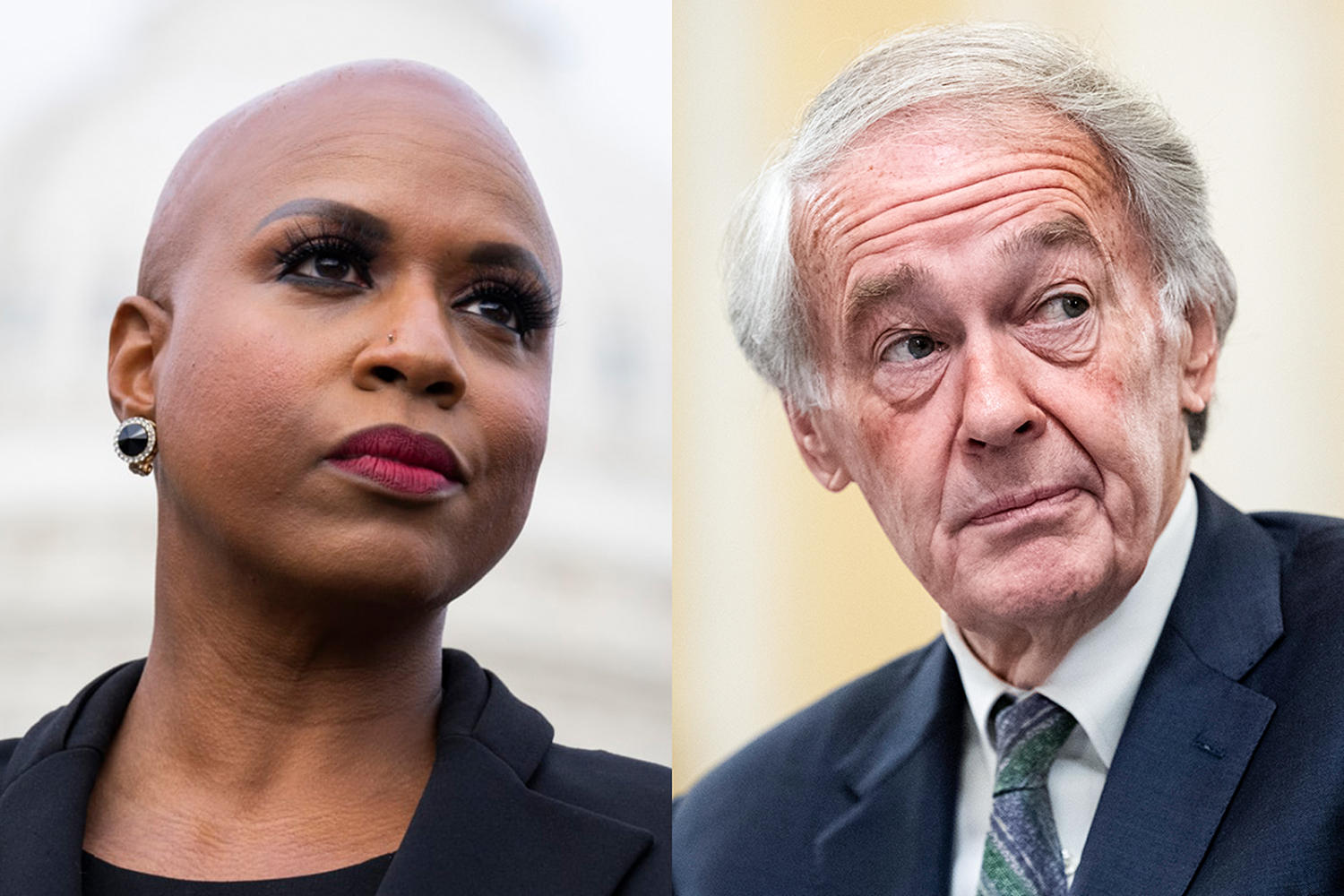

“As we work to reduce the number of people behind bars, we must also ensure that those currently incarcerated have access to clean air, water and living environments, are treated with dignity and respect, and can live in conditions that aren’t dangerous and dehumanizing,” said Sen. Edward Markey, D-Mass., who is partnering with Rep. Ayanna Pressley, D-Mass., and incarcerated members of the African American Coalition Committee at Norfolk-MCI, a prison in the lawmakers’ state.

Pressley said in a statement that the bill “would affirm the fundamental right to a safe and healthy environment for every person behind the wall.”

If passed, the legislation would instruct agencies that oversee federal carceral facilities, including the Bureau of Prisons, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the U.S. Marshals Service and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, to make public the prevalence of and exposure to environmental stressors. Those include examining the temperatures inside of the facilities, some of which lack proper air conditioning and ventilation in the summer months.

The bill also notes how some facilities are located in areas with substandard drinking water or places prone to environmental hazards, such as wildfires.

“Incarcerated people perform labor, such as electronic waste recycling, asbestos abatement, lead paint removal, and forest fire fighting, which exposes them to hazardous conditions without the same level of protection afforded to other non-incarcerated laborers, including protective gear and occupational health and safety protocols,” the legislation reads.

While the bill is largely focused on federal facilities, it also would create a grant program for state, local and tribal carceral facilities to gather data in state prisons and jails that also contend with inadequate conditions. At least 13 states in the South and Midwest lack universal air conditioning in their prisons, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, a research and advocacy nonprofit. And nearly half of all U.S. prisons are situated downstream from water sources likely contaminated with so-called forever chemicals, putting nearly a million incarcerated people at risk of long-term negative health effects, a UCLA researcher said in a study this year.

Advocates supporting the bill say compiling environmental health data at federal facilities is long overdue, and see the persistent racial disparities in prisons and jails and treatment of inmates as part of the nation’s legacy of “environmental injustices” tainting Black and brown communities.

“Incarcerated people get the bottom of the barrel when it comes to food, healthcare and environmental protection. But these inequities aren’t just hurting people behind bars,” William Ragland, an inmate who heads the African American Coalition Committee at MCI-Norfolk, said in a statement. “Toxic prison environments are just a continuation of the pollution that affects many Black communities in Massachusetts and across the country.”