One of the correct clichés about American political campaigns is if you’re fighting the last war, you’re most likely losing.

But what if there’s disagreement over how you won (or lost) the last war?

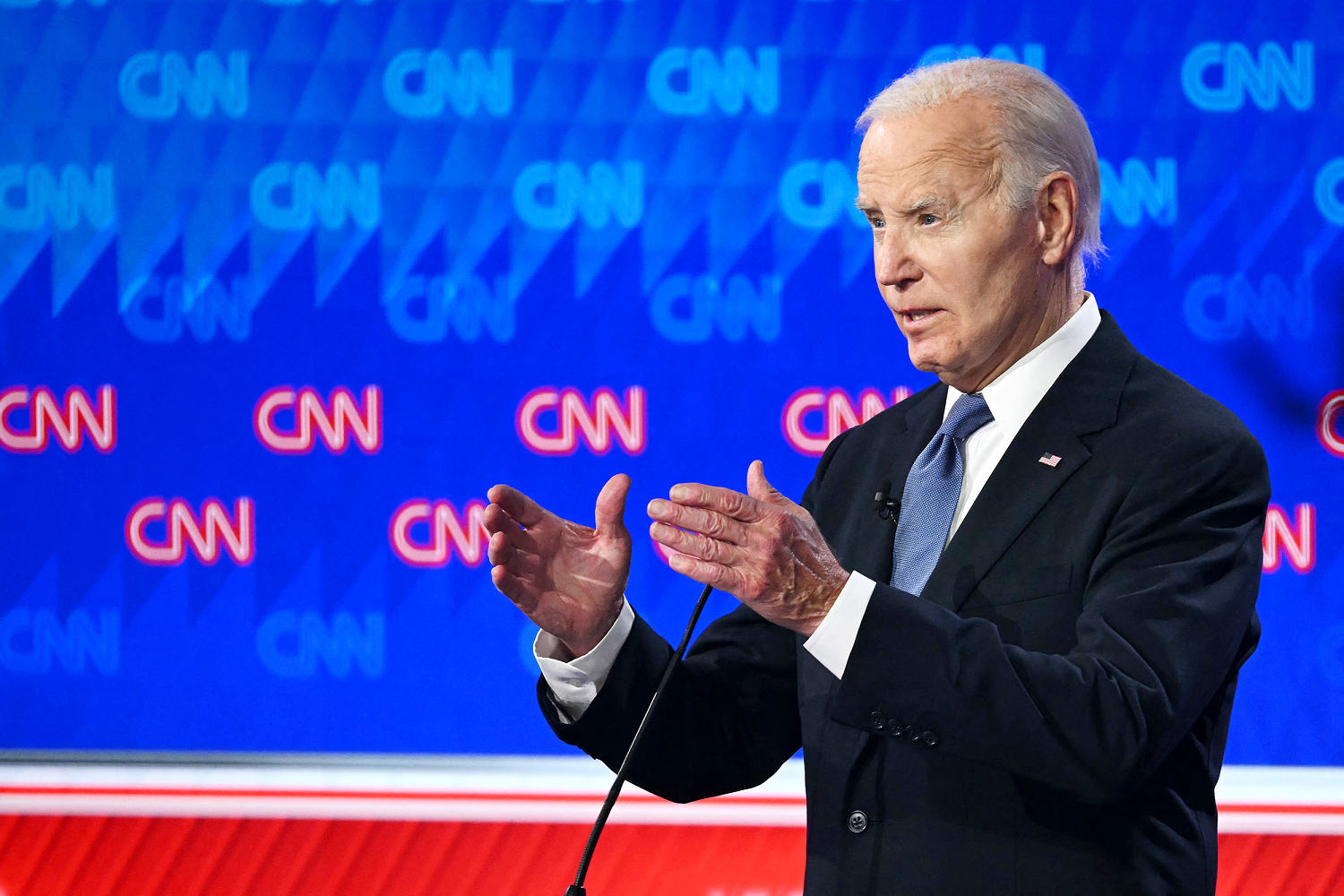

Ultimately, one of the reasons President Joe Biden’s campaign is locked in this moment of postdebate uncertainty is his inner circle’s complete misinterpretation and misunderstanding of both the 2020 and 2022 elections, including how Biden ended up as the head of the Democratic Party. And that misunderstanding has led to a cascading series of potentially fatal positions for the party as a whole in 2024.

Let’s start with the president’s base problem: He has never really had one outside the state of Delaware. Biden’s great strength throughout his political career has been his ability to always be in the “mainstream” of Democratic thinking. He’s not a hard-core liberal, nor is he a closet centrist. He has always been smack-dab in the middle between the two wings of the Democratic Party — slightly to the left of Bill Clinton and slightly to the right of Barack Obama, to pick just two random Democratic presidents out of a hat!

And younger Biden was always good at appearing to be more centrist to moderates in the party and more liberal to progressives. Arguably, his presidency has largely reflected that positioning, as his biggest legislative achievements are pretty reasonable compromises between the progressive and center-left factions of his party.

That positioning also explains why he failed to get traction as a presidential candidate on his own in 1987 and 2008 (or as he was considering running in 2000 and 2004). He has never been anyone’s first choice as a standard-bearer for the Democrats. But what has been key to Biden’s political strength over the years is that he has never been a last choice, either.

Biden has always been “good enough” to be in the mix even without having been the first choice of any of key party factions before 2020. Even organized labor hedged its bets on Biden each time he ran for president, though he was one of its most consistent champions in the Senate (and then in the White House).

That also helps explain Biden’s personal animosity toward the so-called elites — or, more correctly, “the Democratic establishment” — over these last two weeks that his campaign has been in crisis.

Biden is well aware he has never been anyone’s first choice, including when his own running mate and governing partner, Obama, put his finger on the scale for Hillary Clinton over him in 2016. (And in case you haven’t noticed, Biden hasn’t forgotten.) And, yes, that rejection by the Democratic elites over his first 40 years in politics has left a mark.

Then along came Donald Trump. And his approach to politics scared Democrats to the point that Biden’s standing as nobody’s last choice was a feature, not a bug, at a time when the party was looking for a standard-bearer like Goldilocks — not too left and not too right.

Hillary Clinton’s brand was tarnished post-2016, and Biden, as the dutiful No. 2 to the most popular active figure in the Democratic Party, became an easy front-runner for the 2020 nomination.

But let’s look back at the 2020 campaign. The primary campaign wasn’t very good for Biden, despite some attempts at revisionist history. Biden’s events before Iowa looked like previews of our Covid world. There were as many reporters as voters, all standing somewhat apart from one another; In Nevada, I distinctly remember one event where it wasn’t clear it had started, because that’s how few actual voters came for it. If there was a Biden constituency, it was sitting at home, not showing up at Biden rallies.

But Biden’s service as Obama’s vice president finally won him a constituency that ranked him first: Black voters. And then Rep. James Clyburn made the calculation that Biden was his guy, and it was enough to hand Biden not just a win but a dominant one in South Carolina. That one impressive showing — manufactured not by the campaign but by Clyburn (and, in fairness, by a courtship and familiarity with Biden the person over the years) — has fueled a fictional narrative about Biden’s being underestimated.

Biden was never really tested in the primaries after South Carolina, thanks to a desire by all the other candidates not named Sanders and Warren to quickly rally around a non-progressive standard-bearer. Throw in the Covid shutdown and Biden essentially sealed the nomination without much of a fight, a fight that without Trump in the picture (and perhaps without Covid in the picture) would have been a lot more grueling. Would Biden have defeated Sen. Bernie Sanders for the nomination? Probably, because Biden always had the upper hand on the issue of perceived electability. But it wouldn’t have been a cakewalk.

Make no mistake — Biden got that nomination not because of who he was, but more because of who he wasn’t. And the bet many younger ambitious Democrats made by rallying around Biden? They’d have another shot in four years. Why did they think that? Because Biden implicitly said so, by referring to himself as a transitional leader of the party.

Whether Biden believed that or not isn’t clear, but he and the campaign knew that messaging was an easy way to unite the various factions of the party. While he never pledged to serve only one term, he certainly didn’t dissuade folks from thinking that was the plan.

As for the general election, there’s a reason there were so few memorable moments, because they didn’t really exist. Thanks to the Covid lockdown, the general election was all about Trump, from his bizarre daily briefings in the early part of the lockdown to his near-death experience with Covid in the middle of the televised debate part of the campaign. It’s hard to pinpoint a major Biden-driven moment of the general election, outside of “will you shut up, man?” from the first debate.

This was by design. Trump himself complained about it; Biden used a campaign playbook that was essentially prevent defense, four corners, rope-a-dope (pick your sports metaphor), and it worked, barely.

And that’s another feature of the Biden narrative that has been a bit oversold. He underperformed in 2020. He wasn’t much help to Democrats down the ballot. Republicans didn’t pick up seats by accident; clearly there were some anti-Trump Republicans who helped push Biden over the electoral finish line.

The cautious, risk-averse campaign Biden ran to get to the White House became the standard for how he and his team would run the White House. At first, his presidency seemed to be bubble-wrapped because of Covid, and understandably so. Given how close Trump came to death from Covid, this wasn’t an insignificant fear. Covid has always been deadlier to folks over 50.

But one can’t help but wonder whether the Covid cautiousness became such a crutch that it became the norm. The smaller West Wing staff meetings that were a necessity during the pandemic were still operational even after everyone had their shots. The fewer personal interactions with Cabinet secretaries continued. The micromanaging of public appearances with outside elected officials and limited mainstream media access all continued well after Biden himself declared independence from the virus.

This last year, Biden has been more active and has had to undertake more cross-country and international travel, much more than he did in 2019 and 2020. It has clearly taken a toll. Perhaps when the family got together in late 2022 (the end of our first full year post-Covid) to see whether he was fit enough to serve another four years and survive a truly grueling campaign, they misremembered how easy and abnormal 2020 was. From an energy standpoint, 2020 was one of the least tiring campaigns in my adult lifetime. It perhaps gave Biden and his family a false sense of security about whether he could serve four more years.

Biden in 2020 wasn’t the same Biden as he was during the Obama administration, and Biden in 2024 isn’t the same Biden as he was in 2020. His entire political life has been televised, and the clips speak for themselves. I’m guessing nobody has shown Biden or the family these clips, but one can’t help but wonder whether they should.

It was telling that Biden wouldn’t definitively say during his ABC News interview whether he’d re-watched the debate. I’m guessing he really hasn’t watched it in full. Trust me, as someone who is in middle age, I know that most of the time, I see a younger version of myself in the mirror than the rest of the world sees. About once a week, I see my dad and freak out. I don’t like to see that mirror image of myself; neither, I imagine, do the Bidens.

What’s truly hurting Biden now is his own ego. His response to questions about his fitness has been overly defensive. He somehow thinks he’s the victim here. He hasn’t acknowledged why people are worried — they are afraid of another Trump term. Biden hasn’t truly acknowledged that or apologized to his supporters more directly for not being able to go toe-to-toe with Trump.

He asked for the debate, and he has long responded to all the questions about his age with a two-word answer: “Watch me.” Well, a lot of people watched him at the debate, and that’s why there’s widespread panic in the party and among the rank and file, who were keyed into this issue long before late June.

This isn’t about Biden’s feelings; this is about Trump. Hand-wringing about Biden isn’t anti-Biden; it’s anti-Trump. The sooner Biden understands how he got to the White House and why there are so many questions now about whether he should be the Democratic Party’s standard-bearer, the sooner the party can figure out how to move forward.

It’s notable to me that the only Democrats truly embracing Biden right now are the ones who aren’t in much political peril on their own, either because they tend to represent deep-blue states or districts (see “the squad” or Congressional Black Caucus members) or because they aren’t on the ballot (see Sen. John Fetterman of Pennsylvania). Those Democrats with skin in the game are the most nervous, and instead of attacking these Democrats, Biden ought to be commiserating with them.

Of course, there is a flip side to every story. The flip side to this one is how little Trump is benefiting so far from this Biden campaign crisis.

Yes, there has been subtle movement away from Biden in the polls, but that’s the point: It has been more “away from Biden” than “toward Trump.” Trump hasn’t gotten stronger in this moment; Biden has simply gotten weaker.

It’s sort of what happened post-“Access Hollywood” tape but in reverse. Trump’s numbers took a dive in early October 2016, but Clinton didn’t get stronger, and once she became the focus again, Trump regained enough strength to eke out an Electoral College win.

It’s a reminder that while Biden can’t win the campaign at this point, he can still win the election — because his opponent is Donald Trump. And that’s probably the biggest failure of Biden’s presidency.

His actions overseas and his legislative achievements could be key ingredients for Biden to make the case that his style of politics is best for the country. He could perhaps even carve out a new mainstream lane in Democratic Party politics.

But that’s the problem for Biden. He can’t make the case for his presidency himself.

Hard-core Biden partisans think the media should make the case for him, but ultimately, he has to do it, and he has done a terrible job of selling his presidency — in part, because he and his West Wing handlers have been afraid to even let him try. Perhaps he can’t rhetorically do it, but isn’t that part of the job? It doesn’t matter how good a policy is — if you can’t explain it and sell it to the country, you will lose. I’m convinced that in a decade, many of his legislative achievements will be popular, but he has not getting credit now because he has failed to explain and sell them today.

And whether it’s fair or not, many Americans who don’t support Trump disapprove of the Biden presidency because he hasn’t made the country’s appetite for a return to Trump any less appealing. He was elected to turn the page on Trump, and yet Trump is still here and perhaps stronger than ever. It will be hard to ever describe a Biden presidency as successful if he’s succeeded by Trump, no matter how many bills he has signed into law.

One final point to ponder. If, four years from now, America elects its first non-major-party president, we will know why. Democratic leaders have lectured plenty of Republican leaders about their inability to stand up to Trump or to put country over party. And yet, it’s now the Democratic standard-bearer who is acting more and more like Trump all the time. One can’t help but wonder about how things have come full circle when a sitting president calls into his favorite morning show to complain about the media and the elites.

The “double-hater” demographic is growing. And both parties could pay a price down the road for prioritizing their own political ambitions over being the truth-tellers many had proclaimed themselves to be.