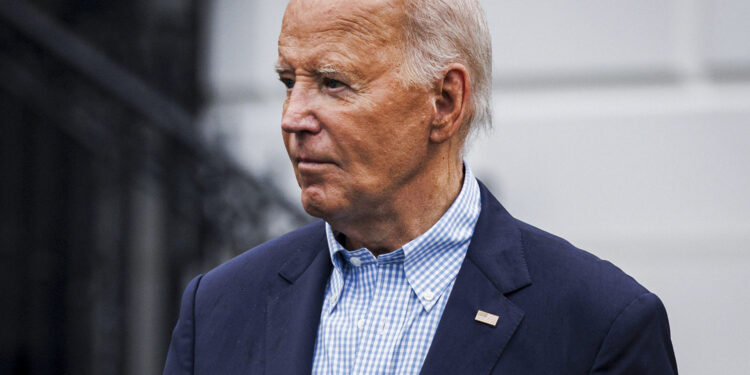

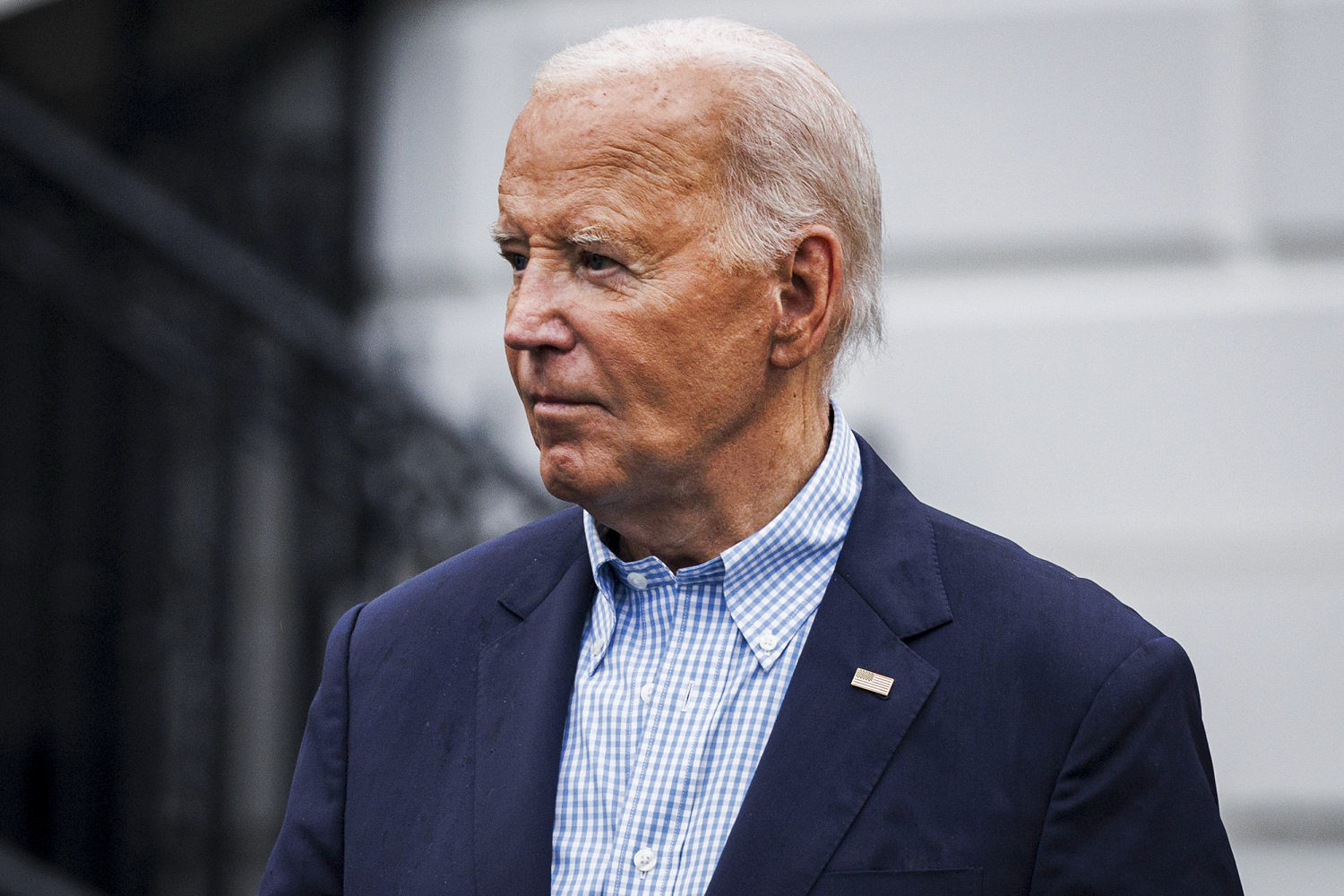

WASHINGTON — President Joe Biden heads into the NATO summit meeting he’s hosting in Washington this week with two distinct challenges, neither of them easy.

On the international stage, he wants to make a case for preserving global alliances in an era when many populist and nationalist leaders are looking inward, his advisers say.

But the tougher task will be on the domestic front, where he’ll need to plow through three days of meetings, speeches and dinners — capped by a news conference Thursday — with the vigor and focus that were noticeably absent during his debate with Donald Trump.

The summit should be a friendly forum for Biden, who is trying to stave off calls from fellow Democrats to drop out of the presidential race after his poor debate showing.

It’s happening on his home turf, so he won’t have to grapple with the overseas travel and late hours that he says left him depleted ahead of the debate.

“He’ll be on an international stage,” said William Daley, a White House chief of staff for President Barack Obama. “This is the first big stage for the president to have since the debate.”

Biden has invested vast amounts of political capital in helping Ukraine beat back Russia’s invasion, and the summit will show how the pro-Ukraine coalition he helped forge remains largely intact.

He and his NATO counterparts will roll out a series of measures to bolster Ukraine’s war machine, White House officials said in advance of the gathering of the 32 NATO member countries.

Leaders are expected to announce deliveries of new air defense systems that will help Ukraine shoot down Russian missiles and drones, as well as progress toward admitting Ukraine to NATO, the officials said.

“Look for some very specific deliverables and announcements about NATO support for Ukraine coming out of this summit,” a senior White House official said in an interview. “There will be some major muscle movements that will prove the point that support [for Ukraine] is still very strong.”

The summit marks the 75th anniversary of NATO, a collective defense treaty that has served as a bulwark against Soviet and Russian aggression in Europe in the post-World War II period. The agreement’s mutual defense clause — known as Article 5 — has been invoked only once, when the U.S. asked NATO allies to join in the response to the Sept. 11 attacks.

Biden will welcome fellow NATO leaders Tuesday night at an event at the Mellon Auditorium, where the treaty was signed on April 4, 1949. The next night, Biden will host a dinner for his NATO counterparts at the White House.

The alliance relies heavily on U.S. funding, leadership and military support, all of which appeared to be in jeopardy during Trump’s presidency. Arguing that the U.S. was getting shortchanged, Trump faulted various European allies for not meeting a commitment to set aside 2% of their gross domestic products for defense.

In February, Trump said Russia could do “whatever the hell they want” to countries that didn’t spend enough on defense, raising the possibility that, if he is elected, he would ignore NATO’s Article 5 provision.

“There’s no question that NATO would be severely at risk, given Trump’s clearly stated disparagement of NATO’s value to the United States,” Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., a member of the Armed Services Committee, said in an interview. “And the same is true of Ukraine.”

Biden has begun reviewing drafts of a speech he’ll deliver at the conference, the senior official said. One message he’s likely to send is that NATO members have ratcheted up military spending on his watch, undercutting Trump’s depiction of some European allies as freeloaders.

When Trump left office in January 2021, only nine allies were meeting the 2% threshold, according to the Biden administration. Today, 23 are.

“The view of many Americans is that the Europeans aren’t doing anything and they’re taking advantage of us and not carrying the load,” James Townsend, a former deputy assistant secretary of defense for European and NATO policy, said in a briefing for reporters hosted by the Atlantic Council think tank. “That case is getting weaker and weaker to make.”

Looming over the summit are crucial elections in the U.S. and Europe. Britain’s new prime minister, Keir Starmer, will join the summit just days after his Labour Party crushed the Conservatives in national elections. His left-of-center party has been out of power for 14 years.

A far-right party led by Marine Le Pen was heading toward a poor third-place finish in France on Sunday, an unexpected result that Biden will surely cheer.

Le Pen said in an interview with CNN that if her party were to gain power, it would prevent France from arming Ukraine with weapons that could strike inside Russia’s borders.

Le Pen’s loss helps fortify the consensus within NATO to protect Ukraine’s sovereignty. Hungary, though, remains an outlier. Its prime minister, Viktor Orbán, met with Russian President Vladimir Putin last week to discuss an end to the war. A nationalist who has befriended Trump, Orbán irked U.S. officials with his trip to Moscow.

“Obviously we were not happy about Orbán’s visit,” the senior White House official said. “But he’s Orbán, and we’ve been dealing with him now for quite some time.”

A separate question confronting NATO is Biden’s fate and the prospect of Trump’s return. Foreign policy experts said they expect the presidential race to be a focus of private meetings and conversations throughout the summit.

Trump favors what he calls an “America First” approach that questions the alliances that the U.S. has forged among nations that share its democratic tradition and liberal values.

Biden will no doubt use the summit to champion the internationalist approach that he favors. An opportune moment will be Thursday’s news conference, assuming he can speak with discernibly more coherence and force than he did during the Trump debate on June 27.

“This is an immense opportunity for him [Biden] to lead with vigor and energy and underscore his commitment to the alliance,” said Ian Brzezinski, another former defense official who spoke at the Atlantic Council briefing.

“He needs to do it not just at the table and closed-door meetings, but by using all the public fora that this summit creates to demonstrate that leadership,” Brzezinski said.

“That’s what allied leaders will be looking for. They’re obviously concerned about what was seen at the debate. This is a major opportunity to significantly reverse that impression.”