Katie Razzall, Larissa Kennelly and Darin Graham,BBC News

BBC

BBCIn 2020, Danish antiquities dealer Dr Ittai Gradel began to suspect an eBay seller he had been buying from was a thief who was stealing from the British Museum.

More than two years later, the museum would announce that thousands of objects were missing, stolen or damaged from its collection. It had finally believed Dr Gradel – but why had it taken so long for it to do so?

The first clue

“The gems that fascinate me are nothing so boring as diamonds,” says Dr Gradel from his attic study, lined with display cabinets of treasures.

He collects ancient gemstones carved with intricate figures or motifs – they help paint a picture of what life was like in the classical world and were often used as jewellery.

It is a niche passion. The circle of dealers is small – so the internet has become a vital trading tool and eBay in particular a rich source of bargains.

Millions of miscellaneous items are posted for sale each day, but on 7 August 2016, something unusual happened.

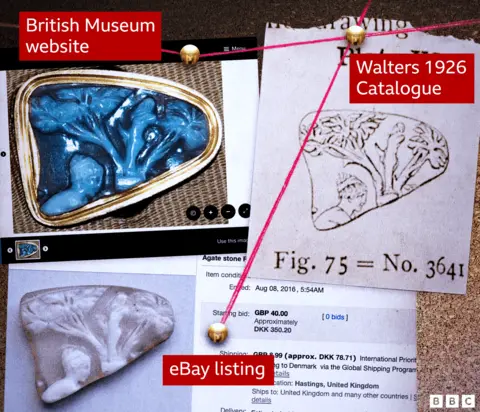

A grey and white piece of a cameo gemstone featuring Priapus – the Greek god of fertility – was posted by a user called “sultan1966” for just £40.

The listing was taken down after a few hours, unsold.

Priapus is one of the more memorable gods – often depicted with his oversized genitals on show. The seller may have hoped Priapus’ brief appearance online had gone unnoticed – but alas not.

It was spotted by Dr Gradel, who says he was born with a photographic memory.

He says the unusual skill has helped him identify rare finds. In this case, it would also help him uncover the identity of a suspected thief.

Dr Gradel had been buying gemstones from sultan1966 on eBay for almost two years. The seller had told him his name was Paul Higgins and that he had inherited the gems from a grandfather. They were being sold at bargain prices but Dr Gradel could tell many were very valuable.

This time, he knew he had seen the Priapus cameo before. He was sure it featured in an old gems catalogue he owned from one of the world’s most famous institutions, the British Museum.

“There was no doubt it was the same object and I was confused,” he says.

The museum has since said in documents filed at the High Court that it believes the cameo had been taken from a storeroom in the Greece and Rome department by a senior curator, Dr Peter Higgs, just a week before it appeared for sale.

Dr Higgs started working at the British Museum in 1993 as a research assistant, having studied archaeology at the University of Liverpool.

Living in an ordinary semi-detached house in Hastings on the south coast, he was later described by the museum’s chairman as a “rather quiet, introverted” person.

Within hours of removing the eBay listing in 2016, the museum believes Dr Higgs logged into its database and attempted to tamper with the Priapus cameo’s catalogue entry.

An estimated 2.4 million items at the museum are uncatalogued, or partially uncatalogued, out of its total collection of 8 million. The museum, which has now brought a civil court case against Dr Higgs, believes he was mostly targeting these uncatalogued artefacts – and that, this time, he had made a mistake.

Dr Higgs would have been able to see the cameo was a catalogued item, searchable by the public and staff alike. It was even on the museum’s website – it was not the kind of item that could disappear and not be missed.

If his tampering had been successful, says the museum in its court papers, it would have hidden the database photo of the cameo from view – but it says he failed.

The next day, Dr Higgs is known to have returned alone to the storeroom where the cameo was kept, the museum says. It believes this was so he could return it.

Thief at the British Museum is available on BBC Sounds and you can watch a documentary of the same name on BBC iPlayer

However, something valuable remained missing – the cameo’s gold mount. The museum believes it was removed by Dr Higgs and sold to a scrap dealer.

The cameo’s value is estimated at £15,000. It would be worth double that, says the museum, if it still had its gold mount.

Dr Gradel says it is “totally bizarre” that he could sit at a computer on a small Danish island and be the first person to discover something was awry at the British Museum.

He wrote to sultan1966, the man he knew as Paul Higgins, asking why the Priapus cameo had been withdrawn. The seller replied saying it had been a mistake – it belonged to his sister, who didn’t want him to sell it.

Dr Gradel chose not to alert sultan1966 about his suspicions. “That would enable him to cover his tracks,” he said.

Instead he decided to keep an eye on him – to see if any other pieces belonging to the museum appeared.

Four years would pass before the next clue – when Dr Gradel would make the shocking discovery that it appeared to be an inside job.

The second clue

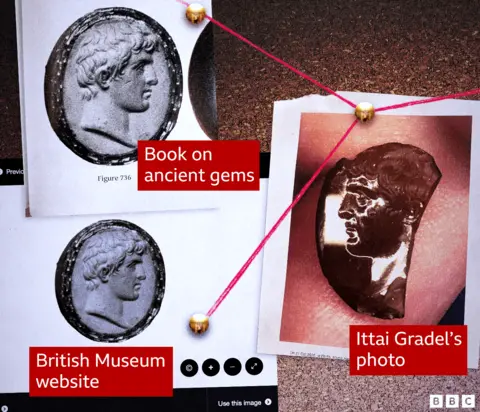

In May 2020, Dr Gradel noticed an image in a newly published book on gemstones.

Figure 736 was a gem featuring a man who resembled the Roman Emperor Augustus. It was labelled as belonging to the British Museum.

The figure portrayed on the gem had an usual hairstyle for the period.

Suspicious once again, Dr Gradel looked through his records.

He matched the image in the book to a photograph on his computer hard drive of an olive-green gem fragment that he had previously been offered for sale by a British dealer called Malcolm Hay.

Dr Gradel told him about his suspicions around the gem right away.

But when Malcolm Hay wrote to the museum to make enquiries about the startling similarity, he was told it was closed because of the Covid lockdown.

“[Deputy Director] Jonathan Williams replied to me, and he said, of course, there’s no way of confirming anything at the moment because no-one could get into the museum,” Mr Hay said. “He asked me to hold it.”

Luckily, the person who had first sold it to Mr Hay happened to be a mutual friend of Dr Gradel’s – a gallery-owner in Bath called Rolf von Kiaer. Dr Gradel got in touch with him immediately.

Rolf replied that he had bought the olive-green gem on eBay a few years before.

The name of the seller? Sultan1966.

At this point, Dr Gradel feared something was very wrong. He began to comb through computer files and paper records of everything he had bought from sultan1966.

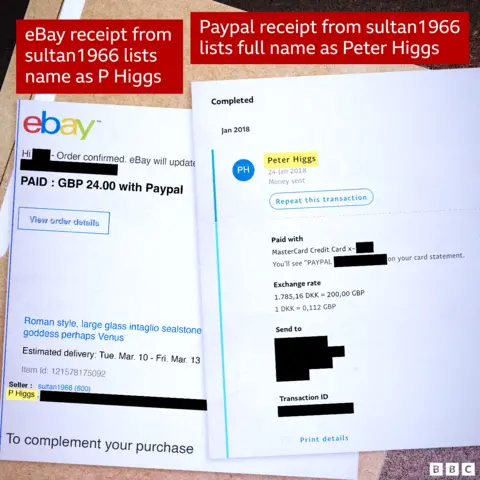

He meticulously went through eBay listings, correspondences and transaction receipts, dating back to his very first purchase from sultan1966 in 2014.

An online receipt provided a crucial clue – apparently revealing the seller’s real name. It was listed as Peter Higgs rather than Paul Higgins.

“A PayPal receipt has to be attached to a real bank account,” Dr Gradel explains. “So this had to be his real name.”

He immediately called Rolf von Kiaer once again.

“[Rolf] then said to me, ‘Ittai, you do realise that is the name of a curator in the British Museum Greece and Rome department, don’t you?’ And I remember that distinctly, my hair stood on end, I was absolutely shocked by this.”

Over the coming days, Dr Gradel continued to unearth new connections between the online seller and Peter Higgs.

He discovered that “sultan1966” was also Dr Higgs’s account name on Twitter – now known as X – and that 1966 was the year he was born.

“The email address on the PayPal account was Bodrum1966,” said Dr Gradel. “His specialty was actually working on sculpture from ancient Halicarnassus in modern day Turkey. And the modern name of that place is Bodrum.”

Finally, Dr Gradel found an eBay receipt for a gem he had bought from sultan1966 that gave a full private address. Dr Gradel decided to check it against property records – and the name given was Peter Higgs, the British Museum curator.

Everything suddenly made sense to the Danish collector with the photographic memory.

“There was no other possible conclusion to draw from this. It was what it seemed to be – that the British Museum curator was pilfering his own museum,” says Dr Gradel.

Dr Higgs has since denied all the allegations and is defending the civil claim the British Museum is bringing against him.

‘Someone could be framing him’

While Dr Gradel was combing through his receipts, Peter Higgs’ career seemed to be going from strength to strength.

In January 2021, he was promoted to acting head of the Department of Greece and Rome, having built a reputation for helping track down stolen antiquities around the globe.

He had been described by the UK government as “a world-renowned curator” in 2015 after helping to return a stolen 2,000-year-old statue to Libya. Dr Higgs later appeared on BBC’s Crimewatch to describe his work.

When Dr Gradel emailed the museum’s management in February 2021 with his concerns about Dr Higgs, he got a return acknowledgement from deputy director Jonathan Williams but that was all.

Dr Gradel was unaware the management had already heard about the allegations against Dr Higgs just a day earlier, accompanied by a warning he might be being framed. Dr Higgs had been tipped off by another archaeologist – Dorothy Lobel King, after Dr Gradel had approached her on social media for advice.

Ms Lobel King had become concerned Dr Higgs was being set up. She had emailed him, and he had forwarded the email on to Dr Williams the deputy director – the court documents now say.

The museum did investigate Dr Gradel’s concerns – but as it did so, Dr Higgs was allowed to keep running his department. He tried to throw colleagues off his scent, the museum says, by altering computer records and implying that items had gone missing decades earlier.

The day after Dr Gradel emailed his allegations, according to the museum’s court documents, it believes Dr Higgs made a report falsely claiming that the olive-green gem, which had been bought by Malcolm Hay, had actually been lost decades ago.

The museum also believes Dr Higgs marked the item as lost in its catalogue entry by inserting a note made to look like it had been written in 1963.

The British Museum chairman, George Osborne, says the museum’s court evidence suggested the thief had gone to “pretty elaborate lengths” to cover his tracks.

In May 2021, Malcolm Hay was invited to a meeting to hand back his gem. He said the museum was not really interested in where he had got it: “They were just happy to have it back.”

Meanwhile, Dr Gradel was growing increasingly anxious that he hadn’t heard anything back about his allegations, despite asking for an update several times.

Finally, in July 2021, he received a reply from deputy director Dr Williams saying the museum had carried out a “thorough investigation”. All objects had been accounted for, he was told, and there was no suggestion of wrongdoing by staff.

Dr Gradel says this was “bizarre to say the least – totally absurd”.

He knew Mr Hay’s gem had gone missing, been bought online and was only in the collection after being handed back. When Dr Gradel tried to find out more, the museum told him details were confidential.

Gouging marks left by pliers

Inside the museum however, that was not the end of it.

In December 2021, a routine spot-check revealed items were missing in the Greece and Rome department and a top-secret second investigation was launched. The following April, a curator was hired to check every single item – although under the supervision of department head, Peter Higgs.

Nevertheless, it was becoming clear that something was very wrong.

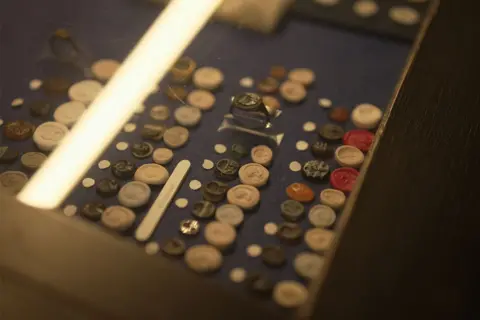

The museum says the hired curator discovered that more than 300 registered items, many with gold mounts, had been damaged or stolen. Some of those remaining had deep gouging and scratches, which looked like marks left by pliers.

When the curator went on to look at the unregistered items contained in one particular storeroom, court documents claim she discovered that 1,161 items were missing – more than three-quarters of its entire contents.

The curator handed over preliminary reports to her boss, Dr Higgs, in late December 2022 and the museum’s court documents claim Peter Higgs tried to delay escalating the findings several times.

At first, he said it wouldn’t be good to announce the news before a weekend or Christmas, the documents claim – then, they continue, he said it was his birthday and he didn’t want to deal with the matter.

But, according to the museum, the curator insisted and her findings quickly made their way to the top.

The museum’s director at the time, Hartwig Fisher, shared the information with chairman George Osborne.

“I immediately said: ‘Well, hold on, that must be linked to that email that I saw a couple of months ago,’” Mr Osborne told the BBC.

They decided to call the police immediately and Dr Higgs was suspended.

“It took us some time as an institution to accept the betrayal of trust that these thefts represented,” Dr Fischer later told the BBC. “Betrayal by an insider has been a hard lesson to learn, and hard to prepare for”.

He later resigned from his position early over the response to Dr Gradel’s allegations.

“I think it was pretty traumatic for the people who were investigating this, particularly as the scale of the thefts emerged,” said Mr Osborne.

Both Dr Higgs’ workspace and home were raided by the Metropolitan Police over the subsequent months.

According to the museum’s High Court documents, police found handwritten notes and printed instructions on editing museum records at his work, while at home they seized items believed to have come from the museum’s collections.

“I’m 100% certain we’ve got our man, we know who has stolen these items,” says Mr Osborne, “missing coins were found in his house”.

Dr Higgs has denied the coins came from the museum, stating they belonged to a dead relative.

He was finally dismissed from the museum in July 2023 – more than two years after Dr Gradel first raised the alarm.

Mr Osborne told the BBC the Danish antiques dealer had done the museum a great service, and he was sorry he had not been listened to initially.

“I hope he can look at the changes… and see that some good has come out of what has been a very sad and unfortunate series of events,” said Mr Osborne.

These include a commitment to catalogue every single item in the collections and tighten security processes, ensuring no member of staff can enter a storeroom alone.

Police say the investigation is ongoing and nobody has been arrested or charged with any offence.

As for Dr Gradel, he has handed back more than 360 gemstones he believes belong to the museum, including some he had sold to other dealers and tracked down to return.

“I encourage everybody who has come by these gems to do what I’ve done and just hand the gems back to the museum,” he said.

The British Museum’s lack of cataloguing means Dr Gradel has had to donate items that were in his possession, while the museum tries to prove ownership.

It is considering how to reimburse buyers who unwittingly bought items online and which it believes are from its collections.

Buyers like Ittai Gradel, who says he is still working out how much money he has lost paying for gems which shouldn’t have been up for sale in the first place.

“I don’t think there’s much more I can do to assist the museum in retrieving gems,” he says. “It’s like a sort of a closure.”

Thief at the British Museum is available on BBC Sounds and you can watch a documentary of the same name on BBC iPlayer