On July 18, 1994, a van loaded with explosives crashed into a Jewish community center in Buenos Aires. The blast killed 85 people at the Argentinian Israelite Mutual Association (AMIA) and wounded over 300. It was the deadliest terrorist attack in Argentina’s history.

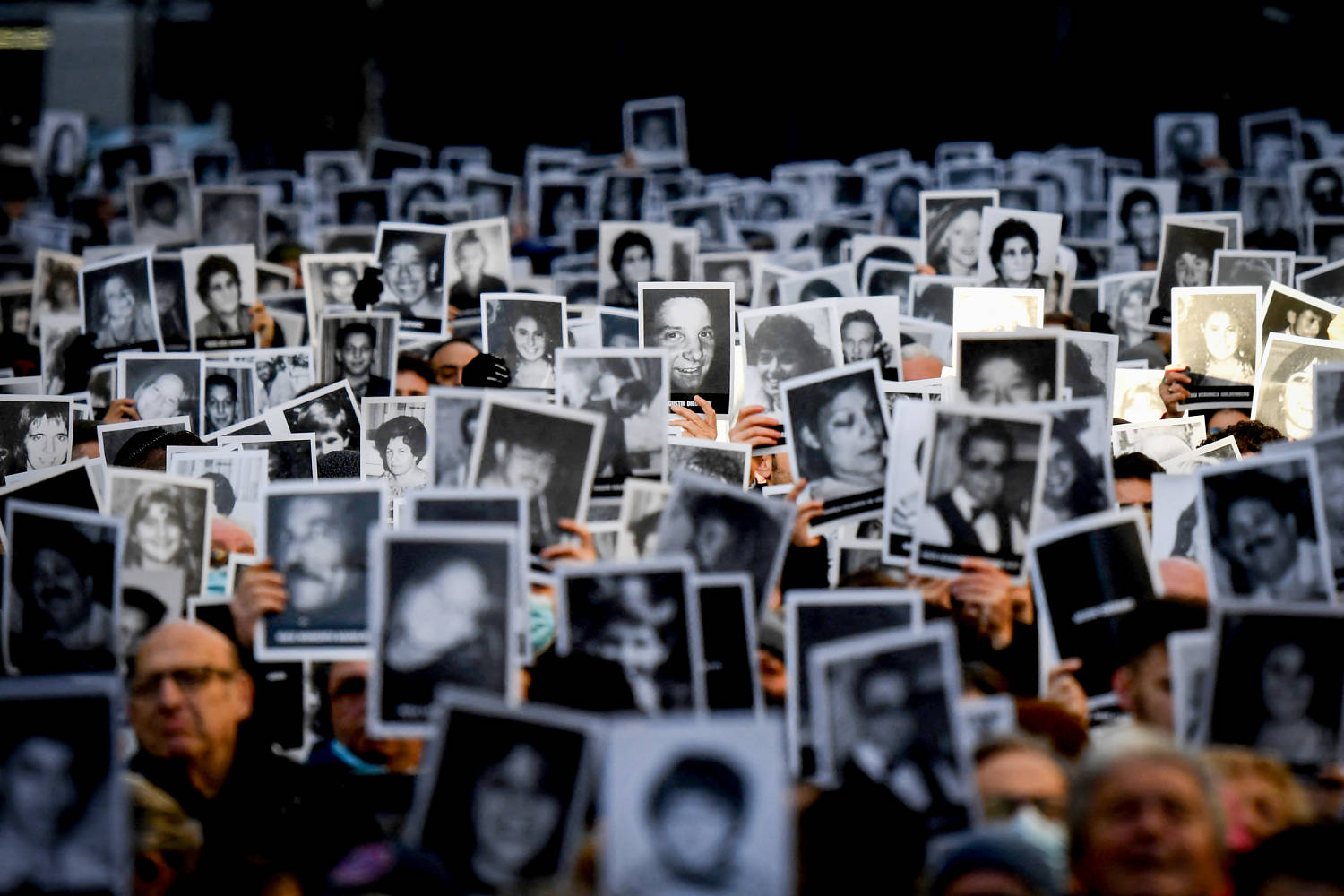

Today, 30 years later, Argentinians will gather in their capital — as they have on almost every anniversary — to remember the victims, and demand justice.

“There is a big push for justice which, as years go by, is like a deafening silence,” said journalist and author Javier Sinay, whose great-grandfather founded the first Yiddish newspaper in Buenos Aires.

Sinay is the author of the book “Después de las 9:53” (“After 9:53”) published by Penguin Random House in Argentina on July 1.

The title refers to the time of the attack and the book focuses on the first 30 days of the investigation, as well as the impact of those days over the next three decades.

“I focused a lot on the first month because I consider it to be a scale model of everything that comes later,” he said.

Sinay explains that the structure of his book is rooted in a 66-page ruling that first established “a why, a how, a who” for what happened, just 23 days after the bombing.

The book is also based on research from other court documents, including 14 folders containing 200 pages each, and media reports, as well as interviews with 26 people involved in the case — including two former intelligence officials off the record and a head judge in the investigation.

In April 2024, a high court in Argentina blamed Iran for planning the 1994 bombing of the AMIA, which Iran’s government has denied. While the court ruling could open the door for the families of victims to seek justice internationally, Sinay said that Argentinians view the decadeslong investigation with distrust: Investigations have not progressed and Iran has refused to turn over suspects.

“There is an idea that less was investigated than what was actually investigated. In other words, society is very pessimistic about the balance,” he explained. “To this day, the attack remains unresolved because no one was found guilty, and those arrested were acquitted,” referring to five men who were charged with involvement in the bombing but were cleared by a court.

This lack of resolution not only impacted the families of the victims and the Jewish community in Argentina — the largest in Latin America — but also contributed to a nationwide culture of distrust.

“I think Argentina sleeps with one eye open,” Sinay said. “In the first month after the attack, a rumor was already emerging that there would be a third attack.”

With “third attack” Sinay is alluding to the 1992 bombing of the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires and then the 1994 AMIA attack.

Over the past three decades, the looming threat made a significant footprint on popular culture in Argentina. And Sinay said it fed into different conspiracy theories trying to connect two high-profile deaths after the AMIA bombing with a third attack.

The first was the death of Carlos Menem Jr., the son of former Argentina president Carlos Saúl Menem, who was in office during both of the bombings. Menem Jr. died in a helicopter accident in 1995, and his father called publicly to reopen the investigation.

Sinay said that conspiracy theorists believe the crash could have been an attack directed at former President Menem.

The Argentinian leader, who had been raised as a Sunni Muslim in a Syrian immigrant family, was also accused of covering up Iran’s involvement in the AMIA bombing and later cleared of charges.

The second was the death of the prosecutor Alberto Nisman. He had led the investigation of the case and alleged that Argentina’s then-president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner tried to block him from investigating Iranian officials.

These conspiracies, Sinay said, have cast a significant shadow over Argentina’s legal system.

“The impunity that exists and has existed is a very terrible thing,” said Sinay.